Discussions in Parliament reflect the intent and will of the people in enacting specific legislations. A small study of just the Joint Parliamentary Committee that finalised the JNU Bill shows how JNU was conceived of an autonomous research institution. Can any set of UGC Regulations be allowed to erase the people’s will just 60 years later? The JPC Report can be found here. jnu bill 1964

On November 1, 1965, the Bill that led to the Jawaharlal Nehru University Act was finally placed in Parliament. Thanks to one of our former students’ efforts, JNUTA has managed to obtain a copy of the report submitted by the Joint Parliamentary Committee set up to examine the Bill, and it shows how much of what JNU is today is in consonance with what was originally envisioned about it.

This 60 page reportchronicles how the idea of JNU emerged from passionate conversations in both Houses of Parliament and how everyclause of our beautiful Act was discussed threadbare. But what should make everyone who has been associated with JNU truly proud is that the University as it evolved has come to satisfy the aspirations and hopes of both the proponents of the Bill as it was passed and those who dissented with regards to aspects of it.

An all-India institution of national importance

One change that the JPC made completely unanimously in drafting the final Bill was to make JNU a university that had an all India research character rather than of an affiliating nature that had the territorial jurisdiction of South Delhi.

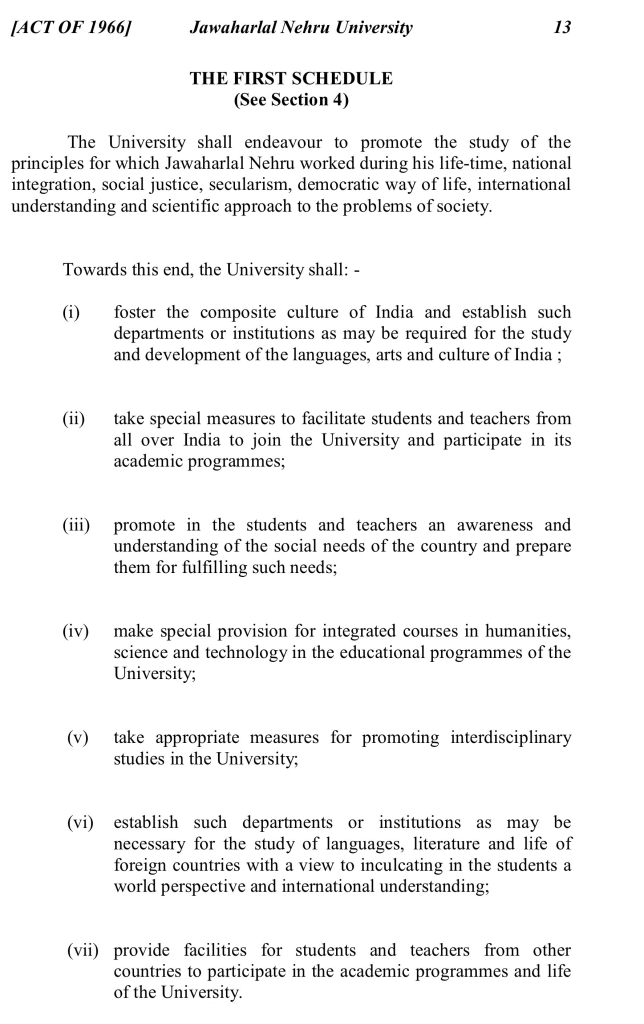

Another change from the original Bill, however, was the statement of the objectives of the university in Section 4: “The objects, of the .University shall be to disseminate and advance knowledge, wisdom and understanding by teaching and research and by the example and influence of its corporate life and in particular the objects set out in the First Schedule”, and the First Schedule itself:

It is this First Schedule that has guided JNU’s development and progress through the next fifty years. From conducting an entrance exam in over 60 centres across the country to low fees to its various integrated programmes of study, to its courses in foreign languages and its deprivation points system, all flow from the understanding that the advancement of knowlege is possible only when inclusion is the basis of education. And the university’s corporate life, at least before 2016, was by and large infused with the same democratic and consultative governance, with Schools and Centres being guaranteed relative independence of functioning. The First Schedule has also guided the social life of the university, predisposing the politics of its various unions and associations to the affirmation of social justice, and an awareness that academics must respond to the “social needs of the country”. Can a minimum standards resolution on an award of degrees really be allowed to undo all this? And what do we say of a Registrar and a Vice-Chancellor who fail to, as required by their office to uphold the JNU Act?

Two Notes of Dissent

The JPC had 28 members, 10 from Rajya Sabha and 18 from Lok Sabha. Four notes of dissent are appended to the report, of which two are extremely interesting, as they tell a tale of how our university came to be shaped not only by its beautiful Act (recommended: please read and compare it to the 2009 Central Universities Act) but also the democratically dissenting voices in Parliament and outside it.

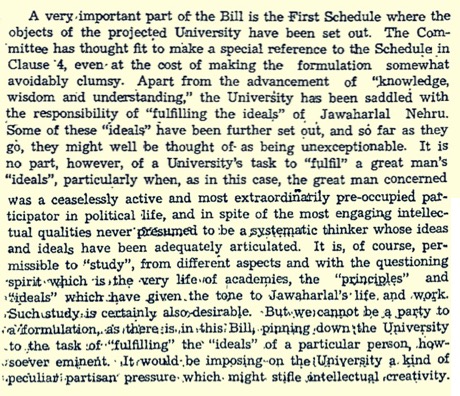

These two dissenting notes — one by H. N. Mukherjee and P.K. Kumaran, and the other by Mukut Behari Lal and Hem Barua — had one thing in common: trenchant criticism about the university being named after Jawaharlal Nehru. For both, the position from which such criticism came was not one of a fundamental ideological opposition to Nehru, but from the idea of what a university must be.

For Mukherjee and Kumaran, a university was not an institution which was to fulfil the ideals and visions of even the most admirable of leaders, but a space for ‘systematic thought’ which must not be subject to any “partisan pressure which might stifle intellectual creativity”.

For Lal and Baria, the very idea was insulting to Nehru himself, standing as he did for independent enquiry, as well as to how such a naming would restrict what a university should study — “a university that must represent all of India in its totality cannot be identified with him.”

Mukherjee and Kumaran also pushed for adequate guarantees that the university would have an all India character and remain accessible to the poor. They specifically propose that “some statutory provision should be made for drawing in students from all the States and for facilitating their study by adequate assistance for poor but meritorious students from different regions of the country.” and “a sufficient number of scholarships and other facilities provided.”

Dissent grew JNU as much as its Act

Although these two observations were but notes of dissent, it is worth pondering over the role that the deliberations they must have engendered had in determining the shape of the university and policies. If there hadn’t been these notes of dissent, what would have JNU been? Did Mukherjee and Kumaran’s demand for a clear statutory provision mould the discussion in favour of deprivation points as a policy decision? Did fees in JNU have remain as low as they have been because of this note of dissent? Did JNU give non-NET fellowships to each admitted research student for the same reason? Is it in true homage to Nehru that there is no Centre for Jawaharlal Nehru Studies, no hagiographic exercises of either celebration of his life and work, and while there is a statue of Jawharlal Nehru on the campus, that took close to twenty years to install. Is it because of this understanding that universities are spaces that must be free of partisan pressure that the hostels are named after rivers, the roads are not even numbered and areas are known by the bus stops close to them; in short, no political figure casts even a shadow in name on the academic autonomy of the university.

What the JPC, an particularly the dissenters knew, was that this Act of Parliament was to give birth to was not only a new institution, but a new kind of democratic space that had to produce meanings whose vitality depended on a different geography, economy and social organisation. It was, in the beautiful words of Mukherjee and Kumaran, something that had to grow “out of the labours undertaken and the values cherished by the academic community”, outside the realm of government control and political interference. Because a university is, Mukherjee and Kumaran say, “a continuing membership of minds devoted to the tasks of learning and of the good life, which someone once defined as being inspired by love and guided by knowledge.”

Both the Act of Parliament that gave birth to JNU and those who dissented from it knew what a university ought to be, and they were proud of an independence that allowed them to even dream of such an institution in the India of fifty years ago. To cull admissions to JNU is of course to damage forever the continuity of this membership of minds and the labours to be undertaken, but is more than that; it is to ‘unwrite’ the history of the dreams of the people of India and the gifts they gave themselves.

Ayesha Kidwai Pradeep Shinde

The JPC report can be found here.

Thanks for this wonderful piece of research: we must build on our institutional memory through many more such exercises. I see this as only the beginning.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wonderful piece of document, which reminds us, what is our character!

Dissent, my lord

LikeLiked by 1 person

Excellent work to reveal the intellectual and moral foundations of the Univerity to the public at large. Kudos!

LikeLiked by 1 person